Features

Published: Irish Times, March 15th 2008Welcome to Brokesville

Ireland 2008: The champagne has been guzzled. The punchbowl is an ashtray. And there’s a strange girl crying in the bathroom. With analysts predicting the slowest economic growth this year since 1991, it looks as though the party is finally over. There’s no avoiding it. As a nation, its time to locate our jackets, make our excuses and flag a taxi back to Brokesville. But there’s no need to despair just yet. In the giddy prosperity of recent years, many of us neglected the sober art of thrift. Now is the chance to learn it anew.

Ireland 2008: The champagne has been guzzled. The punchbowl is an ashtray. And there’s a strange girl crying in the bathroom. With analysts predicting the slowest economic growth this year since 1991, it looks as though the party is finally over. There’s no avoiding it. As a nation, its time to locate our jackets, make our excuses and flag a taxi back to Brokesville. But there’s no need to despair just yet. In the giddy prosperity of recent years, many of us neglected the sober art of thrift. Now is the chance to learn it anew.

For the purposes of this article, I drastically reigned in my living expenses to see how much money I could save. As someone cursed with a Caligula-esque sense of financial responsibility, it seemed like quite a challenge. But I quickly discovered that, even in so-called ‘Rip-Off Ireland’, surviving on a shoestring is as easy as taking out a sub-prime mortgage. All I had to do was shop around, haggle, break the law and generally make a nuisance of myself. Here’s how it went:

SHOPPING

Personally, I wasn’t all that taken with affluence. The foreign holidays were nice. But the clothes were garish, the culture vacuous and the food strange and often confusing. (‘Excuse me waiter, where’s the rest of my dinner?’ ‘Concealed beneath your steak, sir. Restaurant policy.’) Another minor irritation was the creeping gentrification of a raft of our most beloved institutions. Markets, for example, became places that sold only smelly cheeses and obscure vegetables. Luckily, there are still a few left places where the truer, grittier meaning of the word is retained.

It’s 11am Saturday morning and Meath Street, in Dublin’s inner city, is teeming with people. Pensioners and school kids, Old Irish and New Irish – everyone is buying or selling something. Every product known to man is available somewhere on this cluttered strip – and more often than not at low, low prices. According to hand-drawn signs in consecutive shop windows, five euros here will buy your choice of six pork chops, three tubes of Colgate toothpaste, two polyester pillows or one cream ceramic angel. Through one doorway a jeweller is offering 20% off all stock. Through another, a little boy is being fitted for a half price Communion suit.

The Liberty Market itself is a microcosm of the surrounding streets. The bargains here come thick and fast. I pick up three pairs of boxer shorts for four euro, twenty children’s colouring pens for a euro and an 800w two-bar fire for €15. Next I negotiate a deal on such an enormous quantity of kitchen roll that neither myself, my children or my children’s children will ever have to worry about worktop spillages again. At the next stall 8.55kg of Fairy Non-Bio washing powder sets me back just €25. The box is so heavy I have to bring the car around to pick it up.

My most impressive coup though, I think, is five litres (!) of Comfort Fabric Softener for €6. I do a double take when I first spot the enormous bottle. I had no idea there was that much fabric softener in the entire world, let alone available for purchase in a single tub. It takes both hands to heave it into the boot of my car. As I pass, a lady tries to interest me in a selection of tricolour hash pipes. It’s a novel way, I suppose, to combine love of one’s country with love of getting stoned out of ones box. But I’m not interested.

Neither am I tempted by the replica Celtic and Man Utd jerseys (€10 each) at the next stall. They’re obvious fakes. The next thing I stumble upon, though, really piques my curiosity. “What would you call those exactly?” I ask the stallholder. He looks at me sympathetically, as though I were a bit slow. “They’re religious pictures” he says. To be fair, I had worked that much out for myself. One bears the likeness of Pope John Paul II. The other depicts Padre Pio (or “Patrick Pio” as the stallholder calls him.)

But the generic description ‘religious pictures’ doesn’t even begin to do these electronically illuminated monstrosities justice. Dear God… they are tacky enough to frighten the devil in the caverns of hell. Yet, I can’t help thinking that, bundled with the tricolour hash pipes, these hideous items might actually find a niche market on college campuses and so forth. As I leave a man tries to flog me a set of ladies gift watches for fifteen euros. But they’re ugly as hell and I’ve exceeded my budget many times over already. So I hotfoot it away before I change my mind. Away, away… Tonight I bathe in fabric softener!

TRANSPORT

The cheapest way to get around the city is to cycle. And the cheapest way to acquire a bicycle is to steal it. The second cheapest option in Dublin city, I’m told, is to buy a pre-stolen bike at auction in Kevin Street Garda Station. But when I call Kevin Street I’m told the practice has been discontinued. Ashbourne are the boys to talk to, they say. Over at Ashbourne Garda Station, however, no one knows anything about bicycle auctions. And they have no bloody idea why Kevin Street keep directing these inquiries to them, they say.

Finally I’m referred, for reasons unclear, to a second hand car dealership in north Co. Meath. There the trail goes cold. Abandoning the auction idea, I drop by a basement bicycle repair shop on Parnell Street to see if anyone can advise me on where to buy a cheap bicycle. I’m in luck. There’s a girl in her early twenties standing at the counter when I arrive. Her name is Sarah and she’s waiting on a puncture repair. We’re soon joined by an older white haired lady, also wheeling a bicycle with a punctured tyre.

“North King Street?” inquires Sarah. “Yes” nods the older lady. “Bloody glass all over the road.” Glass is a pretty common cause of punctures, Sarah tells me later. Whenever there’s an accident the resulting broken glass is swept to the side of the road for cyclists to pedal over. Punctures are small fry, though, compared to some of the other problems cyclists face on a daily basic. Dangerous driving by motorists and idiots stamping on and buckling the tyres on parked bikes are worries that loom much larger.

But the biggest occupational hazard by a long shot, Sarah says, is theft. In fact, almost every cyclist I spoke to in researching this article had fallen victim to bicycle theft at some stage. No wonder then that buying second hand bikes from disreputable sources is universally frowned upon. Even cyclists who’ve had an expensive bike stolen on them deny ever being tempted to replace it on the cheap. Aside from anything else, Sarah points out, bicycle thieves are often junkies. So any money they make is likely to go straight into the pockets of dealers. Nonetheless, I suppose, if these bikes are being stolen someone must be buying them.

Nothing I’ve heard so far paints cycling in a very positive light. “It’s really not that bad” Sarah laughs. “It’s is good exercise, there are no traffic jams and there’s a sort of camaraderie. You saw the way that woman and I got chatting earlier? Others cyclists always say hello to you and complain about drivers or whatever.” Besides, she says, as a student on a low budget in a city with high rents and a dismal public transport system, there aren’t a lot of other options open to her.

The upside of cycling is that the costs associated with it are miniscule compared to those associated with buying and running a car. The man in the repair shop offers to sell me a men’s mountain bike for €150. That’s less than I spent on speeding and parking fines last month alone, but Sarah advises against buying it. I’ll get something even cheaper, she reckons, if I just put in the legwork. “There’s a guy in Harold’s Cross,” she says. “He’s an alcoholic and… its complicated. But he’d definitely sort you out.” I decide to try another place Sarah recommends, a second hand bike shop just a few minutes walk away on Dorset Street.

She certainly isn’t wrong about the benefits of shopping around. On Dorset Street I find another (to my eyes) identical bike for only €80. I cycle it up and down the footpath. It feels pretty good – I even contemplate pulling a wheelie. The French shop assistant finds me a reflective jacket (€16) and, after rummaging around on a shelf, even out a helmet big enough to fit on my admittedly oversized head (€25). Cards on the table, I say to him. How much for the lot? The shop owner purses his lips. “One ten”, he replies. It’s a deal.

HOLIDAYS

If you’re planning a foreign holiday then shelling out hard currency at some point is frankly unavoidable. But there is one way of keeping those costs to a minimum: House swapping. In theory, it’s as simple as (1) finding someone who lives in a luxury villa, (2) convincing them a fortnight in Mullingar is just what the doctor ordered and (3) Bob’s your uncle. According to Frank Kelly of Intervac Ireland, the popularity of house swapping increased steadily here throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. But with the arrival of the Celtic Tiger the new recruits tapered off.

There are currently about 250 Irish families registered with Intervac. For €85 a year they have access to a database of 8,000 families in over 40 countries with no extra charge for often they avail. For Frank, the beauty of house swapping is that you don’t just have get use of another family’s home. You can also draw on their families, their communities and even use their cars in some instances. Bonds develop, friendships form. “It means you’re a lot more streetwise” he says. “You avoid a lot of the mistakes that someone arriving blind into a place might make.”

In fact, there are other reasons why house swapping might be a more attractive proposition now than it was a decade ago. Perspective swappers no longer have to select properties based on a one-line description in a dog-eared catalogue. Thanks to digital cameras and the internet, its now possible to peruse dozens of detailed photos of each potential holiday homes online before making your choice. And with the advent of cheap flights, house swapping further afield, in the US and even Australia, is a viable option too.

In order to test the water, I decide to see whether my own family home in Ballyhaunis, Co. Mayo generates any online interest. Problem is, I don’t really know how to pitch Ballyhaunis as a tourist destination. It’s my home and I love the place, but I’m not really sure how its charms might be conveyed to an international audience. A quick brainstorming exercise fails to yield many ideas: “East Mayo’s best kept secret… picturesque meat factory and rendering plant… car park an ideal location for pulling hand-break turns…”

So I call Brian Quinn, a senior tourism officer with Failte Ireland West, and ask his advice. “Your location is actually very good” he assures me. “You have access to Galway city, cheap golf, fishing, walking, the whole west of Ireland is available to you there. Remember, visitors from the America or the continent think nothing of jumping in the car and driving an hour or two somewhere. And besides, Ballyhaunis offers that as much Irish culture as anywhere else. Even more so maybe, given that there aren’t a lot of tourists traipsing about the place every day.”

Emboldened, I log onto the website, browse some houses in Tuscany and fire off a few emails. (“Casa bella… Uno bellissimo base from which to explore Kiltimagh, Swinford e Boholla…”) To my surprise, within a couple of days, I receive emails from three families who think Ballyhaunis might be just the exotic holiday destination they’re looking for. It’s amazing. I really never thought it would be that easy. There’s only one question that remains now… How feasible would it be to climb in a box and post myself to Italy?

www.intervac.com

ENTERTAINMENT

Maybe its because I’m a writer, but it strikes me that, if I had written the notice at the entrance to Balbrigan Market, it would haunt me every time I walked past it. (“Anyone sell in Fireworks in the Market will no longer be aloud to Trade in the Market.”) On reflection however, it’s a fitting introduction to a place where rules, of whatever provenance, are seldom followed to the letter. Balbrigan Market in north county Dublin is a cold, mucky and inhospitable place. It’s Sunday morning and the roar of the traffic is so loud that its difficult to think, let alone to figure out whether €10 is too much to pay for a portable DVD player with no batteries. Brown Thomas this ain’t. But if you’re looking for cheap, not-necessarily-legal electronic goods, then you might just be in the right place.

Unfortunately, I’m not the only surprise visitor here today. An Garda Suichana have also popped by. They arrive immediately behind me and, as I’m parking, a man in a tracksuit ducks behind my car for cover. He’s clutching cartons of cigarettes closely to his chest. “You’re not lookin’ for any smokes?” he asks hopefully, as I open the door. Not just now, I tell him. The Garda van waits at the entrance as a squad car patrols the length of the site. Men stand behind completely empty stalls that are festooned with signs saying “4 CDs/DVDs €10, 9 CDs/DVDs €20”. They fold their arms and occasionally shrug their shoulders. Not a bother on them.

There are of course many stalls doing a perfectly legal trade here. But the only purveyor of home entertainment not concealing his stock is a man selling second hand video cassettes. I shuffle through what he’s got. In one box I find the original animated Transformers movie from 1986. It features the voices of Leonard Nimoy, Eric Idle and Orson Welles. It was said of Welles’ involvement at the time that, after decades in freefall, the great auteur’s career had finally hit rock bottom. “How much for it?” I ask the stallholder. “Ten cent” he replies. The critics may have spoken too soon.

“That’d keep her happy for a while, huh?” the guy the next stall says to me, out of the blue. Given that I’m looking at an action figurine, it’s hard to figure out quite what he means. I shrug my shoulders and he nods towards a vibrator that’s lying on the table. “That’d get you in the good books, I’d say” he winks. I ask how much it costs, more out of politeness than anything else. “Three euros. Can’t say fairer.” A cheap thrill, if ever there was one. “Come on” he says. “You have a big wad burning a hole in your pocket, what are you looking for?”

I ask if he has any of those new replica guns that a lot of parents rang Liveline to complain about after the Toys for Big Boys exhibition in the RDS in November. He nods.

“They sound brilliant,” I say.

“They are”, he replies.

He gestures me around to the side of the van and we jump in. He pulls out a stunningly realistic AK47. But it fires 200 plastic pellets a minute, he tells me. Mine for sixty euros, he says. There’s a fifty euro note in my pocket and I’m pretty sure we could do business here. But the Gardai are still at the gate and – all things considered – purchasing replica firearms is quite a departure from the mission at hand. So I hit return to the car empty handed.

FOOD

Smithfield square in Dublin’s north inner city is a place where the contrasting fortunes of modern Ireland are shown in sharp juxtaposition. On one side of the square is an upscale supermarket – its walls adorned with quotations from Frank Lloyd Wright and George Bernard Shaw; its shelves stocked with foodstuffs not customarily eaten with tomato ketchup. It caters to the professionals who occupy the expensive, gated apartment complexes that now dominate the square. Across the cobblestones, groups of hooded teenagers huddle outside the entrance to the Children’s Court smoking cigarettes and growling at passers by.

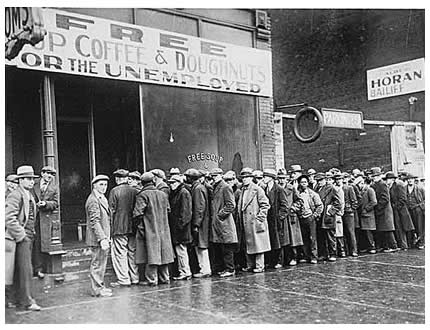

Tucked away discreetly on a side street is the Capuchin Day Centre on. Every day at 8am and again at 2pm a long queue snakes along the wall outside, waiting for the doors to open. Since 1969, food has been provided here six days a week for Dublin’s poorest and most needy. About 120 turn up for breakfast each morning. About 300 for dinner. You don’t have to be Catholic. You don’t have to be Irish. You don’t even have to be poor. “Our principle is we don’t ask any questions,” says Brother Kevin, who runs the kitchen. “Its uncomfortable enough for people to come to a place like ours without us asking them any personal questions.”

The day centre costs €750,000 per annum to run, of which €450,000 is provided by the government. The rest is raised in voluntary donations. The Gardai from the Bridewell Station nearby do an annual fundraiser. At Christmas there is carol singing. The volunteers, Brother Kevin says, come from all strands of society. Civil servants, students, Gardai, nurses, doctors. As for those avail of the service? There is a large Eastern European contingent in recent years, Brother Kevin estimates, but the majority are Irish.

It’s 2pm on a weekday afternoon, and I’ve joined those queuing for food outside. The weather outside is bitterly cold so rush of warm air when I enter the building is comfort in itself. The food served up comes in surprisingly generous portions. There’s a Styrofoam cup of oxtail soup to begin with. The main course consists of three slices of turkey, mashed potatoes and mixed veg washed down with a cup of tea. There’s dessert available but I don’t take it. I’m dressed down and I don’t tell anyone I’m a journalist. But I’m treated with unfailing courtesy by the staff.

The men at my table (like the vast majority here) are male, middle aged and sober. They eat their meals in silence and I don’t feel too much like talking either. To be honest, I feel like a voyeur trespassing in their misfortune. So I eat up quickly and leave a donation at the door on my way out. That afternoon I contact Brother Kevin to tell him I dropped by. He is very keen to know what I thought of the place. I tell him I was very impressed and ask a bit about the people who come in. There’s one man, he says, who has been a regular since the place opened.

The more common experience, especially for immigrants, is come here for a few weeks until either work, or passage home, is secured. Brother Kevin tells me about a Polish man who had trouble getting work when he first arrived in Ireland. He was a regular at the centre for a few weeks. Then one day he stopped coming. After not hearing from him for a few months, the man returned at Christmas and put a large donation into the box. ‘I was hungry’ he said. ‘And you fed me.’ “I thought that was very appropriate,” he says.

My visit to the Capuchin Day Centre is sobering, but also a heart-warming experience. It is a reminder, if one were needed, that while the last ten years have been kind to some in our society, a great many others have not been as lucky. As the more fortunate of us face into the prospect of a minor blip in our incredible run of good fortune, a visit to a place like this puts our woes in some much-needed perspective.