Features

Published: Mongrel Magazine, March 2004The March of the Wooden Soldiers

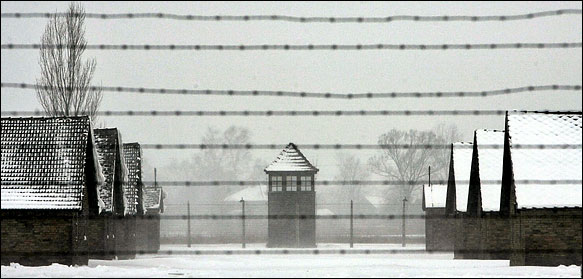

“Forever let this place be a cry of despair

and a warning to humanity, where the Nazis

murdered about one and a half million men,

women and children, mainly Jews,

from various countries of Europe”

Inscription at Auschwitz-Birkenau

THE northern gate at Birkenau is deserted as the taxi driver shoos us out into the snow. We stumble forward, bleary-eyed and dumbfounded by the sheer scale of what’s in front of us. Symmetrical rows of huts stretch out as far as the eye can see, and the barbed wire skeleton encasing them vanishes into the mist in each direction. It’s the world’s largest crime scene and the largest mass grave. And it’s fucking huge. Rob grimaces and pulls a crumpled joint from his jacket. He rummages in his pockets for a light. Antoine sways, mumbles something incoherent and, for a moment, seems to contemplate getting back into the car.

Then we pass through the gates and a hush descends.

This place demands silence now as unmistakably as once it inspired fear. Silence as we trudge across the snow-covered sleepers to where the people disembarked (expecting the worst, said Charlotte Delbo, but not the unthinkable). Silence as we stare at the ruins of the gas chambers where they were murdered, and at the crematoria where their bodies were burned. Silence in the car on the journey back. And over dinner in Krakow we hardly say a word. What’s there to say? Harry had said: “Go there. You should see it.” He was right.

1.

Rewind to eight o’clock that morning and it’s not silence that assaults us. It’s not solemn contemplation that comes blasting out of Harry’s surround sound speakers with such violence that the ashes in the ashtrays dance and the empty cans on every surface rattle. It’s Welcome To The Jungle and it’s fucking loud. “Get up you guys!” he roars. “COME ON, WAKE UP YOU BASTARDS!”

And with the first stirrings of consciousness come the first inklings of remorse.

Rob slumps forward in the armchair and starts skinning up. He mightn’t be awake. He doesn’t have to be. “No way, you fucka!” Harry plucks the reefer from Rob’s mouth. “You can take it with you. We’re going!” Our antipodean host is pissed off. He has a right to be. As houseguests we have all the manners of a marauding medieval army.

Krakow Central Station is hopping. Moustachioed men sell hot food from wooden stalls. Gorgeous college girls mill about the place in every direction. It occurs to me that a strategically timed Lech Walesa Look-alike Contest could effectively paralyze this country. Harry marches us to the counter and buys three tickets on the next bus to Auschwitz. Transaction completed, he relaxes a little.

“Look guys, Ewa’s just going a little bit mental about last night.” He says it like they do on Home & Away: Men-tal.“But it’s cool. I’ll sort it. You just need to get out of here for a bit.” He hands me the tickets and vanishes into the haze, leaving us high and dry in the Friday morning rush hour.

Over breakfast in a nearby cafeteria we take stock. Only a deranged individual would undergo a 70km bus journey in the circumstances. And only a deranged individual with a morbid sense of humour would consider the train a preferable alternative. (“The train to Auschwitz?” hisses Antoine. “Isn’t this little outing grim for you enough already?”) Rob eyes the line of fun-sized Polish beers on the counter behind the till. I shake my head. No, it’s obvious why Harry’s sending us to Auschwitz. It’s the only place in Poland we might actually return from sober.

“We’ll just have to bite it”, I tell them. We take a cab.

Minutes later we’re shooting through the suburbs with our new friend Boguslaw at the wheel. Rob and Antoine are dozing in the back. I’m up front, taking the brunt of the conversation. “Two hundred fifty euro per month my son in Krakow earn, yes? First month in Buncrana is two thousand euro.” Like practically everyone we meet in Poland, Boguslaw has family working in Ireland. His new grandson is even an Irish citizen.

“Of course, Donegal very beautiful. Atlantic Ocean very beautiful. But Spire of Dublin? Why you waste all money on this piece of shit?” He seems to expect some sort of answer. Oh, God… He’s doing about a billion miles an hour. And he’s not too fussy about which side of the road he drives on either.

In Big Sur, Kerouac talks of a hangover so severe that he begins to feel remorse over the birth pains his mother endured bringing him into the world. For a moment, I think I might be on the brink of such a horrorshow. But then slowly – inexplicably – I come around.

He’s actually a bit of crack, old Boguslaw. One thing is immediately apparent: he lives to drive. (Days later, when it looks like we’re about to miss our flight back to Dublin, Rob suggests giving him a call: “He’d do it cheaper than fucking Ryanair. He’d do for the price of the petrol!”) When his children were small he’d drive them to Bulgaria for their holidays each year. To recoup some of the expense he would fill the boot of his car with pairs of Wrangler jeans – which were easier to come by there – and sell them on the black market back home.

He made so much money doing this that he ended up bribing state doctors for sick leave so that he could make further runs. And, because prices for most commodities were fixed, the money he was making was worth a fortune. No wonder he sounds almost nostalgic for communism. Eventually the conversation dries up. “Auschwitz very close now” he says.

2.

Of the three sites known collectively as Auschwitz-Birkenau, only Birkenau was a purpose built extermination camp. The smaller administrative section known as Auschwitz I (with the infamous ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ sign) was originally a Polish military barracks. Although thousands died there, it functioned, ostensibly at least, as an internment camp. The larger Auschwitz III was a manufacturing plant. There the able-bodied were taken to be wrung for labour before being sent on to the gas chambers.

Of the three sites known collectively as Auschwitz-Birkenau, only Birkenau was a purpose built extermination camp. The smaller administrative section known as Auschwitz I (with the infamous ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ sign) was originally a Polish military barracks. Although thousands died there, it functioned, ostensibly at least, as an internment camp. The larger Auschwitz III was a manufacturing plant. There the able-bodied were taken to be wrung for labour before being sent on to the gas chambers.

Only Birkenau (or Auschwitz II) was custom designed for the industrial-scale slaughter of human beings. Well over a million people perished here. If that number is too vast to get a handle on right away, stomping around it a while does offer some perspective.

The outer perimeter fence is thirteen feet high and over five miles long, all around. Within it stood about 250 long wooden shacks. (Less than fifty of these survive today). These draughty hovels were designed to stable fifty horses, but instead slept as many as a thousand people each night. The S.S. ran the place with ruthless efficiency. Trains from all over Europe dumped their wretched cargo on one end of the camp. On the other, in four massive crematoriums, the furnaces burned constantly.

At the height of the slaughter, up to 24,000 people were gassed and cremated here in a single day.

Everything in this godforsaken place – every railroad sleeper, every sprig of barbed wire, every nut and bolt – is mute testimony to the cold blooded nature of the slaughter. It’s fucking disturbing, then, to discover that the camp was built mostly by the labour of the prisoners themselves. Why, I wonder, didn’t they just say ‘No. You may kill me, but I refuse to help you kill others after me?’

It was, I suppose, pretty uncharted territory for humanity. It must have been hard to believe that even the Nazis were capable of such barbarity. Mooching around in their misery awhile though, I still can’t help wondering what else the prisoners might have done. A very small number of them did escape, of course. One man even made it to London. But escape was a long shot. The prisoners were a long way from home and couldn’t necessarily count on the support of the local population.

The ruins of the gas chambers lie in a heap beneath the snow, destroyed ahead of the advancing Red Army in January 1945. I wonder what it’d have taken to knock one of them out of action. It would have cost you your life to find out. But death was the likely next step whichever way you turned in this place. If you could have taken out one of the gas chambers on your way, you would at least have put a spanner in the works of this awful machine, if only temporarily. The slower the S.S. were able to kill prisoners the more would be alive when the Russians arrived. And while this place was operating at full capacity the Russians were most definitely on their way.

A few kilometres down the road at the Holocaust museum I discover that this is pretty much what did happen. On October 7th 1944, about three hundred Jewish Sonderkommandos blew up crematorium IV using explosives smuggled into the camp. They fought off the S.S. for as long as they could with stones, improvised grenades and even machine guns. By nightfall the revolt was crushed and all of the insurgents dead. But despite their heroism that day, many Jews still regard the Sonderkommandos as traitors for assisting the S.S. in the running of the camp.

It is claimed that they only revolted when they discovered that they were about to be exterminated themselves.

The museum is tough going. In one corridor we come across an old lady intently examining a line of mugshots on the wall. Stopping at one young man’s photograph, she takes a rose from her bag. She tries to wedge it into the narrow gap between the frame and the wall. But she’s old and she’s frail and it’s too high for her to reach. I stand a few feet behind her desperately hoping some member of her family will materialise to assist her. When no one appears, I reluctantly step forward and she hands me the flower. I slide the stem into place and she nods absently but barely even notices me. She’s a thousand miles away.

The mammoth piles of confiscated shoes and clothes are horrific, but it’s the suitcases that are really upsetting. There are thousands upon thousands of them with names and addresses printed neatly on the sides: Bermann, Goldstein, Kafka, Morgenstern.

One of the torture devices in the infamous Block 11 catches my eye. It’s a wooden frame about six feet high. Prisoners would first be handcuffed (with their hands behind their backs) and then hung up by their wrists from this apparatus, with their legs dangling in the air. I notice it because recently I read about a suspected Iraqi insurgent named Manadel al-Jamadi who died after being interrogated in this way by the CIA in Abu Ghraib prison in November 2003.

The museum walls are adorned with pious quotations from dignitaries who’ve visited here through the years. All agree that what occurred here must never be allowed to happen again; that wherever evil rears its head again the righteous nations of the world will mobilise to bring swift and impartial justice. Does anyone seriously believe that? Similar atrocities have happened many time since and will happen again.

Even Auschwitz survivor and Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, who has campaigned against genocide in Cambodia, Rwanda and the Balkans, pointedly refused to condemn the barbaric Israeli assault on Sabra and Shatila in 1982. (He said he felt “sadness with Israel, not against Israel.”)

Maybe Max Von Sydow’s character in Hannah and Her Sisters said it best, when he mocked the intellectuals who agonise over how the Holocaust could have happened. “Given what people are”, he sniggered “the real questions is ‘Why doesn’t it happen more often?’”

3.

Back in Krakow, Harry has been busy. First he convinced Ewa to go visit her parents in the countryside for a few days. (Well, not exactly. First he made her breakfast and cleaned up the apartment. Then he convinced her to go home to her parents.) Next he did the rounds of the local wise men. Now he’s back home cooking dinner and bouncing off the walls.

Some of his mates have dropped by to meet us. They’re fellow ex-pats, TEFL types. Nice lads, if a biteen harmless. Bottles are cracked open and introductions made, but Rob and Antoine have renounced the power of speech. They ensconce themselves within a cloud of smoke, leaving me once again to host the show.

The main thing I remember about this dinner is that we’re sat on one side of a large table and Harry’s friends are on the other. They have these wide expectant grins, like they’d heard about these crazy Irish guys and they’d turned up for a helping. And I’m sinking, sinking, sinking…

An American guy, called Brad or Chad or something, asks me what I thought of Auschwitz. I tell him it was a real barrel of laughs. He just nods politely. I ask if he’s ever been there himself. He hasn’t. But he definitely intends to some time. I tell him he should, they do a two-for-one cocktail promotion in the museum bar. Wow, he says, he’s surprised they have stuff like that in a place like Auschwitz. But it might be weird to sit there partying in a place where all those people died. “I guess you Irish guys like to drink, huh?”

Harry’s a perceptive fucker. Usually I have to fight him tooth and nail over the music we listen to. Tonight he sits at the PC putting together a playlist composed exclusively of song he knows I like. “Jack he is a banker and Jane she is a clerk / Both of them save their money and when they come home from work…”

I get to thinking about Ireland, about how Yeats once despaired of us for believing that we were born to pray and save. Now we don’t even bother with prayer. We snapped out of Catholicism like a drunken stupor. A three bedroom semi-detached in Tyrelstown – the measure of my dreams! Oh, God… Harry catches my eye and gives me a discreet nod. I’ve got a feeling I’ll come around.

4.

It’s Saturday night and we’re barrelling down the street on our way to a club, where Harry’s friend is DJing. We’ve picked up a little entourage along the way. One of their number, an affable older guy called Joe from Belfast, is regaling us with deranged anecdotes about his sexual escapades across the former Soviet bloc. Our progress is stalled by a beautiful, smiling girl in the middle of the footpath.

She’s looking for directions to the Hotel Grand – although, as Harry points out, she’s actually standing right in front of it. She continues smiling. It’s like she is already very fond us for some reason. She really is beautiful, but she couldn’t be any more than fourteen years old. “I think she’s a prostitute” mutters Rob, somewhat unnecessarily. Joe moves straight in. “How’s about ya, love?” He gives her a squeeze and they link arms.

We start moving again. “She might be a bit young… do you not think…?” someone says. Joe doesn’t answer, so Harry lets it go. It takes me a moment or two to comprehend what’s going on. “But she’s just a kid…?” The big guy is smiling broadly. “And?” he asks. Neither of us really appreciates, I think, that the other is quite serious.

The penny drops.

“She’s a fucking kid, you arsehole!” Joe turns around sharply. He wouldn’t be averse to kicking the shit out of me. But he’s the outsider here and he’s outnumbered so he smiles and says “Nah, nah, she’s fucking, whadiyacallit, nineteen or twenty.” “No she isn’t!” I look around for some support. But the lads want to be sitting in the warm club, not freezing their balls off on the street.

Harry reluctantly intervenes. He talks to the girl in Polish (although he later says she was probably Belarusian) and asks her age. She just smiles and shrugs her shoulders. The issue is surely settled. But Joe is defiant. “She’s fucking nineteen or twenty.” By now he’s copped it that no one else really is that bothered what age this girl is. In fact, most of them reckon that I’m the one causing the problem.

He gets up in my face like a caricature or a grotesque hallucination. “What you gonna do about it, bucko? You gonna call the cops, you cunt?” We’re starting to attract attention now. “Cos maybe the cops would have more business talking to you boys than to me?” I punch him hard in the mouth, but it’s like he sees it coming before I do. Because he lands two blows in retaliation before I’ve even realised I’m in a fight.

Mayhem ensues. I score one more punch against him before Harry and Antoine pull me off, inadvertently leaving me open for his third. This one really hurts. Everyone’s going crazy now. Harry’s mates are shouting to get the fuck out of here. Harry’s telling Joe to get lost, to just get lost. The young prostitute scarpers down a side street and Joe disappears after her.

I have no intention of following them but Harry pins me against the wall anyway. “THEY WILL LOCK YOU UP, MATE. THEY WILL FUCKING LOCK YOU UP IN THIS TOWN. TURYSTA OR NO TURYSTA.” I push him off me. He pushes me back. “You fucking dick” he sneers. “If she didn’t go with him, she’d have only gone with some other fucka’. What the were you gonna do, huh? What the fuck were you going to do?” I don’t have an answer.

Humiliated, I strike out alone back toward the Market Square. Although I’m burning with anger, I’m relieved to hear Antoine pacing after me. Already I realise I have no clue where I’m going or what I’m doing. He pulls up alongside me and guides me into a cafe a few yards up the street. I put my head down and duck into a dark corner toward the back. Antoine goes to the bar and by the time he gets back I’ve got it all worked out.

There’s no way of putting any logical order on it so I tell him everything, the whole story: line by broken line, row by jumbled row. I let it all out. I even mention Nietzsche at one point. Antoine listens in silence. He’s sympathetic and all, but he really doesn’t give a fuck. Eventually, I ask what he has to say for himself. “Your nose is bleeding, mate” he says, with a benign, narcotic smile. “Go to the bathroom, clean yourself up.”

When I get back, I notice we’ve got company. “Eoin, this is Magda and and this is Alina” says Antoine. “When they finish college in the summer they’re thinking about moving to Ireland. Why don’t you should tell them about the, ah, whadiyacallit, the two-for-one drinks promotions…”

Photographs: Antoine Roquentin